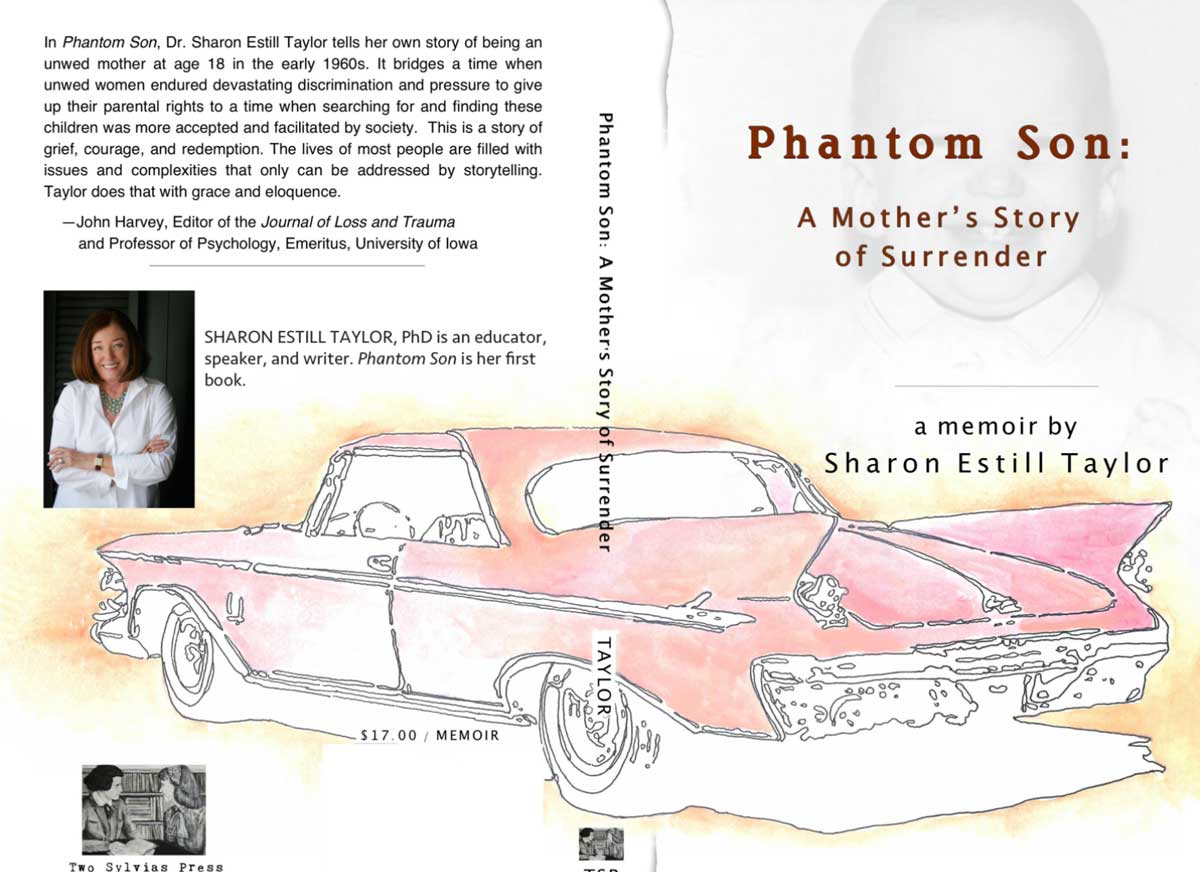

PHANTOM SON: A Mother’s Story of Surrender

A book truly comes to life in collaboration with a team of high creatives. In this case, they include, Two Sylvias Press, artist James B. Hartel’s illustrations, the web design of Igor Brezhnev, and everyone who encouraged me to tell the story that was never intended to be told. In 1964, this was a shameful tale with no blessing from society and no resolution for the terrible choice a mother had to make. But, I did it another way.

A very long time ago, I won an award on which these words are engraved: “Come to the edge,” he said, “though we might fall. They came to the edge and he pushed them. They all flew.” I’m still flying and I hope you will join me.

—Sharon Estill Taylor, PhD. Author, Educator, Speaker

Order Phantom Son Today!

Praise for Phantom Son:

A Mother’s Story of Surrender

Dr. Sharon Estill Taylor has written a highly readable and illuminating account of her experience as a birthmother in the sixties. With a keen eye for detail and a wry sense of humor, she vividly recounts the ways the no-questions-asked cultural forces of the time swept her toward the surrender of her son. Though steamrolled by a process that gave her no say, Dr. Taylor persevered and found her voice as an early champion of sensitive search and reunion.

—Jim Gritter, author of The Spirit of Open Adoption, Lifegivers, and Hospitious Adoption

In Phantom Son, Dr. Sharon Estill Taylor tells her own story of being an unwed mother at age 18 in the early 1960s. It bridges a time when unwed women endured devastating discrimination and pressure to give up their parental rights to a time when searching for and finding these children was more accepted and facilitated by society. There are smaller sub-stories, including one about the author’s loss of her father who was killed in World War II, and how that event affected her family over the decades; and another about her experience of sex and identity-formation in the 1960s. These sub-stories are fascinating and contribute to the gripping nature of this book. Beyond all, this is a story of grief, courage, and redemption. The lives of most people are filled with issues and complexities that only can be addressed by storytelling. Taylor does that with grace and eloquence.

—John Harvey, Editor of the Journal of Loss and Trauma, and Professor of Psychology, Emeritus, University of Iowa

I just finished reading your book. My perspective, or review, may be different because I lived some of it with you, not all of it, but some of it. I found it written from the heart. You exposed yourself to all, friend or stranger alike, to see you and feel the pain you obviously felt. While I read the book I could hear your spoken words only as a brother could. You wrote like you talk, I could hear your voice as I read the book. Probably because I know you. It was well written, again from the heart, and I hope all that read it understand that. I also see the tenacity in you, displayed in the writing of this book as in most things you have done in your life, for example the search for your father in Germany, and working for a doctorate degree in your 50’s. When you set your mind to do something, you do it. No goal is too high for you. Most people tell themselves that” I cannot do that”. You tell yourself you cannot fail. You should have been a Marine!

—Mark Ravely, Sharon’s adopted brother

Dr. Sharon Estill Taylor’s account of her unintended pregnancy and her subsequent traumatic adoption process in the 1960s is an important reminder of how far we have come as a society in terms of the acceptance of out of wedlock births. Instead of the rampant shaming and secrecy surrounding these pregnancies, these commonplace events are now tolerated and even celebrated. This is how it should be as the impact of societal and religious silencing and shame heaped upon these mothers in the 1960s was nothing short of traumatic abuse, as Dr. Taylor tells us in her book. This is an important read for anyone, but I particularly recommend this book for those whose lives have been affected by the disenfranchised grief of coerced adoption.

—Deborah Stokes, PhD, Director of The Better Brain Center, Washington, DC

In Phantom Son, Dr. Sharon Estill Taylor shares her journey as an unwed mother in the 1960s and her courageous search for the son she had to give up. Her grief and loss give way to the formation of wonderful familial relationships. In the tradition of the Irish story teller, Dr. Taylor gives her readers a powerful gift that will resonate in their own lives.

—Fr. Kilian J. Malvey, O.S.B., Professor of Theology, Saint Martin’s University

As a reunited adoptee, I never tire of reading about reunions. In Dr. Sharon Estill Taylor’s Phantom Son, the reader experiences the author’s journey from love-struck teenager to expectant mother to powerful advocate for other birthmothers. Dr. Taylor vividly describes how she was forced to physically separate from her son and how she kept the emotional connection alive in her soul. Dr. Taylor’s writing is raw, open, and honest; important qualities when dealing with such emotional subject matter.

—Christine Murphy, author of Taking Down the Wall

Unwed teen mom finds her voice: Triumphs over 1960s-era cultural stigma

American WWII Orphans Network

AfterWords

Phantom Son swirls around main events culminating in an ending. As with every story, there are more layers added after the original telling that lend deeper color, new insight, and reflection upon the consequences of telling it. (In this case, a story that was never supposed to be told at all.) These AfterWords provide a wider view that will expand over time. Think of it as the ‘then what happened’ part when you read a book you like and you don’t stop at the end but read all the stuff that comes after that. You may even hope the author has written more books.

Epilogue: May 15, 2015 (5.15.15)

Fifty one years and three months later, a beautiful smart young woman graduated from high school. Her parents gave her a party at their dock on the lake where they live. Her younger redheaded brother was there along with her older redheaded sister and her cute boyfriend. Our graduate is a blonde more like her mother and her grandfather’s youngest daughter. Her parents invited all of her friends and some of theirs. Her Kansas grandmother was there as were her uncles who are her father’s brothers, and her mother’s family from Nebraska. She wore a sweet Lily Pulitzer dress and her new pink pearls from another grandmother. It is that grandmother’s tradition to give her granddaughters pearls for graduation, which they appreciate. Someone else was there, too, which surprised and pleased everyone, especially the pearl-giving grandmother whom she calls Nana. Her Nana and this other person are her father’s birthparents. She’s always known that her redheaded daddy has two sets of parents, birth and adopted. She’s known them all her life. So, it’s a good thing when everyone, including both grandmothers -one is Grandma and the other is Nana – and her father’s birthfather are all together. It gives everyone something to see and discuss and act normal about. It’s not such a big deal now, but she noticed that her daddy looks happy and that there were two people there, besides his three kids, who look just like him. This isn’t the first time they’ve all been in the same place, nor will it be the last.

It was a glorious Kansas evening with sparkling water, a Bald Eagle fly-by, a cloud and sky show, and a magic trick that brought people together who should have never known each other.

My Adopted Brother

Not all parts of Phantom Son survived the innumerable edits and tweaks necessary to bring it into the world. This one hit the cutting room floor for reasons of relevance to the book. And, the fact, I think, that I was being asked nicely to step down from my soapbox. This is a tiny story about my brother, Mark, with whom I share the status of adopted sibling.

Since I’d been raised with an adopted brother who intruded upon my seven-year old idyllic only-child life, I was familiar with how adoption felt from the other side. I was also adopted by the father who raised me when he married my widowed mother. I attended their wedding as a four-year-old spectator and it felt perfectly fine to have a new daddy to call daddy. Despite my parents’ best efforts, I also felt separate from my original family – separate and different – spaces in my reality that just didn’t include me.

In our family, adopted kids were told they were “chosen” and it was how my parents grew our family. I overheard my mother and her best friend, Martha Kennedy, speculate about the four-month old baby who appeared one day in late 1952. They believed that his beautiful curls and chubby legs meant he was a prize baby only to be given up under the most dire circumstances. I heard that the foster mother had grown “attached” to him and I remember her crying when she handed him over. As he grew, he continued to be that same sweet, but fearless, boy, minus the chubby legs and curls. The truth is, he more closely matched the coloring in our family than I, a redhead, ever would.

Decades later when that same brother and I were sitting on the floor of a bank in Arkansas, examining the stuff in our now-dead parents safety deposit box, we discovered his adoption papers. I remember his face, I think I read his mind, I certainly felt his heart.

In the wake of this discovery, he claimed his adoption papers and began to search for his birthmother. I was a decade post-search myself, so I encouraged him, even if the results were dire. At least, I said, you will know something. Men are less likely to do this kind of search, I’d learned – boy adoptees less likely than girl adoptees to search for their birthmothers, but my brother was more curious than private at that moment. He was also a cop and he had access to state records.

He began his search, at my urging, exactly where we picked him up at the Michigan Children’s Aid Society. In the end, he found his birthmother through his aunt and, in so doing, discovered an entire family complete with siblings, cousins, grandparents, aunts, uncles, rattling skeletons in the closet, and a birthmother who denied him access to all of it. I felt responsible for his disappointment and sad for his birthmother’s fearful denial of this wonderful man who would never know his people. Mostly I felt deeply sorry for his loss, but less sorry that he knew what he knew for whatever it was worth. Years later, he found a sister with whom he shared a mother and she has welcomed him fully and with love. I now share my brother with another sister but he assures me that my position as #1 sister remains.

Forward in Reverse

I offer the original forward to Phantom Son written in 2009 or thereabouts. This somewhat overly dramatic introduction to Phantom Son, which was then titled, A Color Coded Memoir. These words were set aside for what is included between two covers and a drawing of glorious be-finned Pink Imperial. Thus, here is looking forward in reverse:

“The road back to that time will be forever overgrown with tangles of memory and blurry sensations. If seen at all, it would twist back on itself. The way there would become impenetrable just like the truth of what happened. Though truth itself in 1964 was yet to emerge, it hovered around the next war, ready to spill over in great washes of blood, relief, and tears.”

I wrote those sentences in an effort to record a major event in my life, to preserve the secret of it, and to remind myself that I had come through to the other side. I found these fading words preserved on narrow-lined notebook paper in my mother’s copy of The Best Loved Poems of the American People. They are written in green ink in obedient Palmer Method style, probably with the old Parker fountain pen I’d dragged around since the 1950s. When I wrote with such teenage drama and prophecy, Vietnam had blown up the revelry of the past destroying families with death notices and irretrievable sons. The Beatles called together a new society that would construct a stage upon which a paradigm shift would appear.

The Vietnam war was the first televised war. It included daily press coverage of body bags and battlefield casualty footage, and the only life-changing thing since the assassination of President Kennedy. I was paying attention. Boys my age whom I didn’t know, were proposing to me in beer bars in Denver where you could buy 3.2 beer at eighteen. For a brief time, marriage (to anyone) would earn a deferment from active duty. Speaking of war, when I got to my college dorm in Colorado, I met a girl whose father was the three-star general and aide to General Westmoreland, the boss of the war. She came to Colorado from Saigon, where she’d lived in an American compound, and impressed us with her stories of servants and wild adventures. She called herself a military brat with a free spirit. She, like me, wasn’t a virgin, and was still in love with her high school boyfriend. We thought we were in a minority but no one else was talking. Virginity and sex were a closely held shameful secret. The good girl/bad girl thing was a deeply held archaic belief. Gloria Steinem hadn’t yet appeared to rescue us from that level of ignorance.

She inspired me to embrace my free-spirithood, as I’d been too long in the shackles of adolescence and parental repression. Unlike my friend, beneath my emerging identity, I was guarding a big secret and the attendant shame and fear of discovery. As a freshman who should have been a sophomore, I embraced all my relative freedom, considering the Sisters of Loretto kept us in the dorm on weeknights, back in the dorm at midnight on Fridays and Saturdays, and forbidden to wear slacks or godforbid, blue jeans, anywhere on campus. I didn’t own a pair of blue jeans until 1972 when I met my husband, who was enjoying his incarnation as a hippie bookseller.

I was enjoying a reincarnation of sorts in the fall of 1964. Everything was a lark and a celebration of what I perceived as true freedom albeit with bumpers provided by the nuns, my parents, and my aunt who lived across town. My emerging wings weren’t flight worthy, but I would test them anyway. I was breathing the sweet air of survival. Since everyone had the same restrictions I did, and I had experienced what absence of freedom did to my soul, I believed that life was finally and forever perfect.

That was then, but this story is about now. It’s a fantasy really, unlikely to happen today, but stark reality in the 1960s. I was just out of the vortex my life became between May 1963 and February 1964. Nine months of a fiery ride, defined by overgrown tangles of pain and loss, joy and discovery. Then, I was told to forget.

This is a timeless story told in the languages of loss and discovery. I am grateful for that, for all the women who have summoned the strength and conviction to come forth and speak about their lost children, their lost motherhood. For those who don’t, can’t, or won’t, you’re one of us and we are here to show you the way if you need a guide.

Ours was a collective of brave women forced or choosing compliance to pay a price set by some unwritten code. It seems ridiculous now and worthy of a display in a museum. No one would believe it except us.

This is a trip back in time, as romance reverses, and then rights itself, proving it will never be lost.

About The Publisher

Two Sylvias Press was founded in 2010 by poets Kelli Russell Agodon and Annette Spaulding-Convy. Two Sylvias Press draws its inspiration from the poetic literary talent of Sylvia Plath and the editorial business sense of Sylvia Beach. They are dedicated to publishing the exceptional voices of writers.

Contact Information:

PO Box 1524,

Kingston, WA 98346

twosylviaspress (at) gmail.com

www.twosylviaspress.com